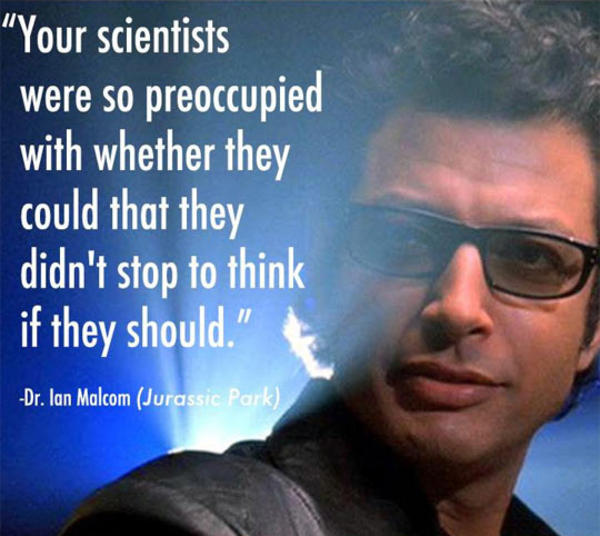

I'm gonna deviate from my norm a little bit, and instead of talking directly about my personal experience, I'm gonna talk about something that is deeply relevant to all scientific studies, because you need to know about it. That's right, we're talking medical and scientific ethics. First, lets get the meme out of the way.

While my opinion of that character and his "chaos theory" can be summed up by John Hammond, this quote is a pretty good representation of WHY we need to study medical ethics. Any graduate

Probably the most commonly cited place to start with this conversation is Henrietta Lacks and the HeLa cell line. You can read her story here, here, here, and here as well as this recent Nature editorial, Henrietta Lacks: science must right a historical wrong (the last two links are the ones that primarily address the ethical issues). I would also be remiss not to mention the book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot.

In short, when Henrietta Lacks was treated for cervical cancer in 1951, samples of both healthy and cancerous tissue were given to a clinical researcher at Johns Hopkins Medical Center. This researched discovered that the cancerous cells would replicate endlessly, whereas healthy cells had a limited number of replications, and would cease dividing after that point.1 The HeLa cell line became the first immortalized human cell line and the benefit of this cell line, and other immortalized cell lines that we learned how to make through the study of HeLa cells, to modern science and medicine is absolutely incalculable. Here's the problem: Henrietta Lacks never gave consent for any of this. It wasn't until decades later that her family even knew about any of it.

Now, you may be thinking something along the lines of "well, this was wrong, but where's the real harm in it?" That's probably what the surgeon and scientists involved thought, if they bothered to ask themselves that sort of question at all. If you want a existential answer, I'll refer you to a fantastic speak by Commander Riker in the Star Trek: TNG episode Up the Long Ladder, but for a visible and tangible harm, consider this: the HeLa genome is available online. That means that the entire world has access to much of the genetic information of her children and grandchildren, whom are alive today. This is one of the most profound and personal violations of privacy possible. Imagine the entire world knowing that your family carries a gene that pre-disposes you to Alzheimer's, or that you are a carrier for the gene that causes cystic fibrosis? The core of scientific ethics is consent, and neither Henrietta Lacks' consent nor that of her family was ever obtained for any of this, and that is a lasting stain on all of science and medicine.

We like to believe that incidents like this are the exception, not the rule. Unfortunately, this is not the case. In 1966 Dr. Henry Beecher published an article in The New England Journal of Medicine detailing 22 examples of published studies in reputable journals with gross ethical violations, starting with the Tuskegee experiment, and including at least one experiment where patients were intentionally injected with cancerous cells without being informed of the nature of these cells. Interesting NEJM has that classic article behind a paywall. However, it is available with commentary here through a Bulletin of the World Health Organization. I strongly recommend that every medical student, nurse, EMS provider, and anyone even tangentially involved in healthcare research read this. This is where we come from. This is what we MUST be better than. The ethics of study design is a pretty broad topic, and I think I may write another post on it later, but for now, let me leave you with some questions to ponder. Can someone who doesn't really understand the potential consequences of a treatment consent? When is it ethical to have someone consent on behalf of a patient who is unable to do so (in a coma, or under anesthesia for example)? What power dynamics might make consent impossible to obtain (for example, can a prisoner consent to participate in medical research)? At what point do incentives to participate in research become coercion? These are tough questions. Although we do have standards for most of these, I don't actually have answers to these questions, which is why we always need to keep them in mind, and keep asking them.

Be well, and remember

CONSENT IS MANDATORY,

Faxe MacAran

1) It is now a known property of differentiated animal cells that they can only divide a certain number of times before they become senescent, after which they cease dividing and die. One of the hallmarks of cancer, arguably the single defining trait of cancer cells, is the ability to continue replicating indefinitely without limit or constraint. An "immortalized" cell line is a normal cell line that has been transformed in some way to give it this property. None of this was known in 1951. At the time, it was mostly just known that human cells could not be cultured indefinitely outside of the body, but that Henrietta Lacks' cancerous cells could.

Comments

Post a Comment